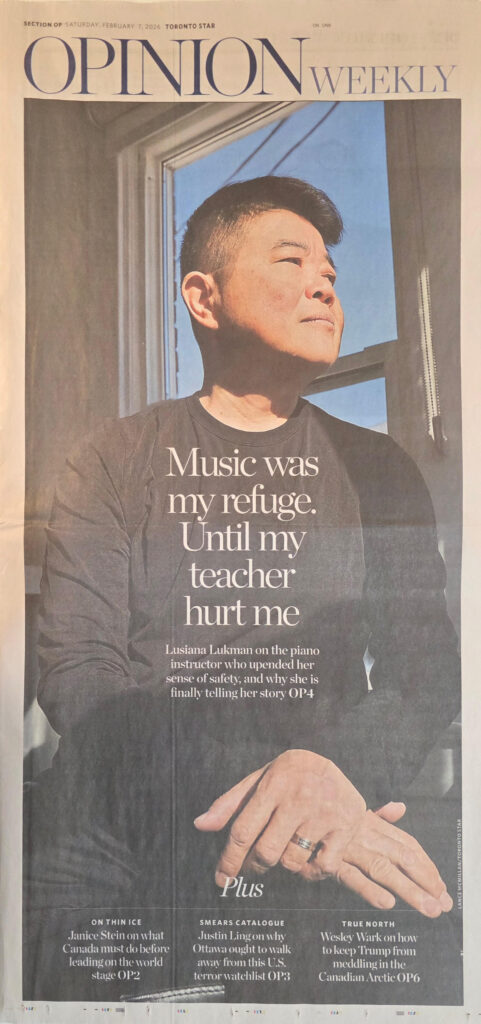

Trigger warning: this article contains explicit descriptions of sexual abuse

Lusiana Lukman: Boris Berlin sexually abused me during my piano lessons when I was 15

February 7, 2026 | 6 min read

By Lusiana Lukman Special to the Toronto Star

Many years ago, a woman called me and asked if I would join her in complaining about a piano instructor at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music, who she said had sexually abused her when she was his student.

I believed her. I, too, had been abused by this teacher. His name was Boris Berlin, and he was a legendary music educator whose instructional books remain a staple for learners of piano to this day.

He began abusing me when I was only 15 years old, a recent visa student from Indonesia who barely spoke English and didn’t have any family or friends here. Like many serious music students, my future depended on my teacher’s approval. He had tremendous power over me, and he exploited it.

Though I believed this woman, I could not bring myself to join her fight. I regret that now. I have come to understand in the years since that a great many students, in conservatories around the world, have been similarly exploited; that so many of us silently carry the shame; and that abusers thrive in this silence. I was not ready to tell my story then. But now I feel it’s important that I do.

***

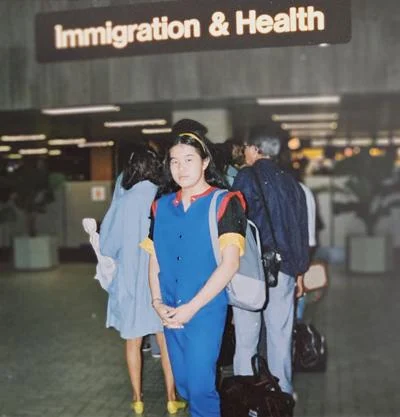

I came to Canada to study music in 1985 when I was just 14 years old.

Music had always been my happy place. In Jakarta, I went to a lovely school, a second home, a safe place. When my home life was not so great — and it often wasn’t — I would go to the school where things were bright, full of music, friends and joyful memories. I saw music as a refuge.

As I reached my teen years, I knew that I was gay, which is dangerous in Indonesia. So I asked my mother to let me go to Canada in search of a new safe space to study music. She agreed, came with me, and helped me settle in.

My mother chose Boris Berlin as my instructor because he was the most expensive teacher at the RCM. “He must be the best,” she said. Back then, there was a published booklet with a list of teachers’ names and their hourly fees. He was also becoming quite famous with piano students around the world: he wrote the beginners’ piano books that were the series being used in Canada and elsewhere.

Berlin started teaching at the RCM in 1928; by the time I was taught by him in the 1980s, he had already been teaching for more than 50 years. He died in 2001 before the ceremony honouring him with the Order of Canada was held.

Berlin was around 78 years old when I first started taking classes with him. When you take a one-on-one piano lesson (or in any classical music studies) the relationship you have with your teacher is not only intense and close but very vulnerable. They tell you what to work on, how much to practice, what to play. They have the power to make your day, or make you miserable. They can make your career or ruin it.

I remember the room where I took lessons with Berlin very clearly. He had a vertical filing cabinet next to the door of his studio. When I was in the room, he would open the door of that filing cabinet so it would block the tiny window onto his studio. No one could see in.

Like any piano teacher, he would sit beside me and correct my hand position/posture. But soon, his hands started moving. During our sessions, he began touching my breasts, and other parts of my body. Eventually, he took my hand and forced it down his pants to touch his erect penis. He used my hand to rub his penis very firmly, then proceeded to take his penis out and tried to get me to do more.

Days before each of my piano lessons, I would get a stomach-ache. I would have nightmares. I couldn’t sleep. I would practise my piano but couldn’t play well. I still had to function through classes and maintain good enough marks so that my student visa permit would be renewed by the RCM every year. It was mental and physical agony, but I thought that I just had to “deal with it” and move on.

I always wondered how many others had been molested like me.

Eventually, I became aware of whispers and warnings.

I didn’t want to talk about what he was doing — I thought it was somehow my fault. But when I squeamishly told a friend or two about what Berlin had done, and that this was happening at almost every single lesson, I was told I wasn’t the only one.

A close friend urged me to report the abuse. We set up a meeting with the RCM’s Director of Academic Studies, Peter Simon, who was responsible for all student complaints. I asked my friend to accompany me to the meeting and she agreed.

We sat in front of Simon. The room was cold and bare other than the desk he was sitting behind and the two chairs my friend and I sat in. I felt very scared and small.

I told him in detail about the sexual abuse.

When I was finished, Simon asked if I wanted a different teacher.

That was all he said.

I was dumbfounded. I felt invisible and dismissed. As if the words that had been so difficult for me to say had never even been uttered.

That was the only conversation anyone at the RCM had with me about the sexual abuse I experienced there.

I was left with a feeling of tremendous shame. Even after gathering the courage to speak up, I was ashamed that I was a victim, ashamed that I was unable to stop it. Ashamed that even after finally speaking up, I was disregarded, ignored, discarded.

(Contacted late last year by the Star, Simon said he was “very sorry to say that I don’t remember the meeting and the incident.” Simon said that his role at the time did not relate to disciplinary action, but that he would have treated such allegations “with the utmost seriousness” and “reported them to my superiors.”)

I tried for so many years to just block out this episode of my life. But it was hard. I couldn’t change programs, not as a visa student. And so, every day, even after changing teachers, I had to go back to where the abuse had occurred, where Berlin still worked. Every day, I was in danger of running into him. My anxiety ran high.

And then, one day, it happened.

The RCM had a huge elevator that was used to move grand pianos. It was larger than the bedroom I had for many years. It was ominous, creepy and cold.

I was alone in that large elevator. The door opened and Boris Berlin walked in. It was too late for me to exit as the door closed in front of both of us. My heart was racing, my whole body felt cold. He turned to me and said, “You know, those things I did to you, it was to teach you, you know that, right?”

(A spokesperson from the Royal Conservatory of Music did not respond to the Star’s questions about whether the institution was aware of any allegations of assault made against Boris Berlin. It offered the following statement: “We are deeply troubled and saddened to learn of Lusiana Lukman’s personal account and acknowledge the immense courage it takes for people to share their experiences. We do not tolerate abuse in any form and recognise the serious and lasting impact it can have on survivors. Creating a safe and supportive environment for our community of students, teachers, and families is of paramount importance to us.”)

***

If you look at the surface of my life, things seem to have turned out just fine. I became a piano, theory and composition teacher. I received my Master’s degree in music composition from the University of Toronto and started my own music school, the Classical Music Conservatory, on Roncesvalles in 1997.

It’s been more than 40 years since I was first abused by Boris Berlin.

But it wasn’t until I read in the Philadelphia Inquirer about the abuse suffered by violinist Lara St. John at the famous Curtis Institute of Music that I finally started to confront my past. I wrote to St. John. She responded, asking if I would be willing to be involved in her documentary, “Dear Lara,” about sexual abuse in famous music conservatories all over the world. Abuse by powerful teachers like Berlin, of vulnerable students like me.

This time, I agreed.

I agreed because of the huge weight of shame, because of all the sleepless nights, because of all the illness, because of other victims’ suicides.

That shame should not be carried by us — it should be carried by the perpetrators, the pedophiles, the rapists, the abusers. It should be carried by those who covered up and protected them. Children should be protected. Victims should be heard and believed. I knew that I needed to get help, to find the tools to deal with this shame I felt.

I love music, I love teaching and I love sharing the joy of music. I decided to start my own music school to do just that. I want students, especially children, to learn in a joyful and safe environment. I want them to have mentors and teachers who inspire, who treat as sacred the trust their students put in them and the responsibility of sharing the beauty of music.

Life can be hard. Music shouldn’t make it harder. Music should be a way to heal.

The world premiere of Lara St. John’s documentary ‘Dear Lara’ was at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival on Feb. 6, 2026.

Visit https://www.dearlara.film/ for more information.